8. Francis of Assisi and Thomas Aquinas - Leaders in Mediaeval Christianity

In the context of political, economic and social changes during the High Mediaeval period, and the

shape of Europe at the beginning of the second millennium, two (almost contemporary) figures

stand out: Francis of Assisi and Thomas Aquinas. There were very different. Both had profound

impacts on church history (including our time) and the development of theological understanding.

We live in an era when people are sceptical of miracles, Divine power and truth. We need to

learn how to embody the Good News. Francis of Assisi's way of life is instructive. With the

Gospel as his rule, he sought to follow in Jesus' footsteps as a peacemaker who travelled light,

welcomed strangers, loved outcasts and living in community. We are challenged to consider how

to better embody the Gospel in our day. There is something remarkable in Francis' life, so that,

eight hundred years after his death, he is memorialized by the three orders he inspired, which

include at least a million members, both Catholic and Protestant; and by four million people who

visit his tomb each year? Thomas Aquinas, on the other hand, continues to attract millions of

Catholic scholars, through his extensive theological writings and their application to life.

Compare the Francis-like Pope Francis (Jorge Mario Bergoglio, known for his concern for the poor,

dispossessed, outcast) and Thomas-like Benedict XVI (as Cardinal Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger he

headed up the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, formerly known as the Supreme Sacred

Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition). A reflection of the body/soul dichotomy.

Francis of Assisi (1181-1226)

Background

Francis of Assisi was an Italian Catholic friar ("brother") and preacher. Originally destined for a

career as a knight, he was converted through illness, a pilgrimage to Rome, a vision and listening

carefully to the challenge of Jesus in Matthew 10:7-10. Though he was never ordained to the

Catholic priesthood, he is one of the most highly regarded religious figures in Christian history.

Francis' father was a prosperous silk merchant. Francis lived the life typical of a wealthy young

man, even fighting as a soldier for Assisi in a campaign against Pisa. However, he became

increasingly disillusioned with the world. According to one account, he was selling cloth and

velvet in the marketplace on behalf of his father one day, when a beggar came to him and asked

for alms. At the conclusion of the business deal in which he was engaged at the time, Francis

abandoned his goods and ran after the beggar. When he found him, Francis gave the man

everything he had in his pockets; needless to say, his family was not impressed.

While on his way to a war in 1204, Francis had a vision that directed him back to Assisi, where he

told his family and friends that he had lost his taste for his worldly life and was looking for more.

He spent time in solitary places, asking God for enlightenment. By degrees he took to nursing

lepers, the most repulsive victims in the poor houses near Assisi. During a pilgrimage to Rome, on

one occasion he joined the poor in begging at the doors of several churches there. The

experience moved him to choose to live in poverty. In the midst of this, he claimed to have a

mystical vision of Jesus Christ in the country chapel of San Damiano, near Assisi, in which the Icon

of Christ spoke to him, ordering him to "go and repair My house which, as you can see, is falling

into ruins." He initially took this to mean the ruined church in which he was praying, so he sold

some cloth from his father's store to assist the priest to achieve this objective.

Francis' father, Petro, attempted to change his attitude to adopting the religious life, first with

threats, then with beatings. In the midst of legal proceedings before the Bishop of Assisi, Francis

renounced his father and his inheritance, laying aside even the clothes he had received from him

and left home in an old cloak and a rope belt from a scarecrow. For the next couple of months he

lived as a beggar in the region of Assisi. Returning to the countryside around the town for two

years, he embraced the life of a penitent and helped restore several ruined chapels in the

countryside near Assisi, among them the Porziuncola, the little chapel of Saint Mary of the Angels,

which later became his favorite abode.

The Beginning of the Franciscan Movement

In 1209, Francis heard a sermon that changed his life. The text was Matthew 10:9, in which Christ

tells his followers to proclaim that the Kingdom of Heaven was at hand, that they should take no

money, nor even a walking stick or shoes for the road. Francis was inspired to devote himself to a

life of poverty. Dressed in a rough garment, barefoot, and with no money, he began to preach

repentance. Historians tell us that Francis was known to be kind, which was one factor in

attracting followers. He was soon joined by a prominent fellow-townsman, the jurist Bernardo di

Quintavalle, who contributed all that he had to the work. Within a year Francis had eleven

followers; they wandered around the hills of Umbria preaching, working part-time, reaching

ordinary people. Francis taught his disciples that the life of poverty saved them from the cares of

the world. He chose not to be ordained a priest and the community lived as "lesser brothers,"

(fratres minores in Latin). They lived poor and preached on the streets, choosing to own few

personal possessions; their base was a deserted house in Rivo Torto near Assisi.

Francis' preaching to ordinary people was unusual in that he had no license from the church to do

so. In 1209 he composed a simple "rule" for his followers ("friars"), (the Regula primitiva or

"Primitive Rule") which emphasized following the teachings of Christ and walking in his footsteps,

in particular caring for the poor and the sick; this took courage, given the virility of frequent

mediaeval plagues. Later that year, Francis led his followers to Rome to seek permission from

Pope Innocent III to found a new official religious Order; according to tradition this occurred on 16

April 1210 (the Pope had serious misgivings at first).

One of his first followers was Clare of Assisi. While hearing Francis preaching in the church of San

Rufino in Assisi in 1209, she was touched by his message and realized her calling. On the night of

Palm Sunday, 28 March 1211, Clare sneaked out of her family's palace. Francis received her at the

Porziuncola and established the Order of Poor Ladies, later called Poor Clares. This was an Order

for women, and he gave a religious habit similar to his own to the order, before lodging them in a

nearby monastery of Benedictine nuns. Later he transferred them to San Damiano, where they

were joined by other women of Assisi. For those who could not leave their homes, he formed the

Third Order of Brothers and Sisters of Penance. This was a community composed of people whose

members neither withdrew from the world nor took religious vows; instead, they carried out the

principles of Franciscan life in their daily lives, intersecting with the community around them.

Francis encouraged his followers to live by the Gospel they preached, surely a better way to be

"salt" and "light", as Christ intended, than separating ourselves from the world.

Mission Outreach

"Preach the gospel, and if necessary, use words" (Francis of Assisi)

Determined to bring the Gospel to all God's creatures through what we today would call

missionary work, Francis sought on several occasions to take his message (and his order) beyond

Italy.

Francis stressed the importance of translating the Scriptures into languages people spoke every

day, so that preachers could use them to communicate the Gospel, rather than using Latin. He

and his followers learned to write and use poetry to convey the message. He encouraged his

followers to learn other languages, so that could reach others with the Christian message. In the

late spring of 1212, he set out for Syria and Jerusalem, but was shipwrecked by a storm on the

Dalmatian coast (off what is today Croatia), forcing him to return to Italy.

On 8 May 1213, Francis was given the use of the mountain of La Verna (Alverna) by Count Orlando

di Chiusi, who described it as "eminently suitable for whoever wishes to do penance in a place

remote from mankind." The mountain became one of Francis' favourite prayer retreats. In the

same year, Francis sailed for Morocco, but this time an illness forced him to break off his journey

in Spain. Back in Assisi, several noblemen (among them Tommaso da Celano, who would later

write Francis' biography) and some well-educated men joined his Order. In 1215, Francis went

again to Rome, for the Fourth Lateran Council. During this time, he probably met Canon Dominic

de Guzman, who later founded the Friar Preachers, another Catholic religious order. In 1217, he

offered to go to France. Cardinal Ugolino of Segni (the future Pope Gregory IX), an early and

important supporter, advised him against this and said that he was still needed in Italy.

In 1219, Francis went to Egypt in an attempt to convert the Sultan and to put an end to the

conflict of the Crusades. This was a brave step, given fear of Muslims on the part of Europeans,

and mutual animosity occasioned by the Crusades. The visit is reported in contemporary Crusader

sources and in the earliest biographies of Francis, but they give no information about what

transpired during the encounter beyond noting that the Sultan received Francis and that Francis

preached to the Saracens without effect, later returning unharmed to the Crusader camp. One

detail, added by Bonaventure in the official life of Francis (written forty years after the event),

concerns an alleged challenge by Francis offering to submit to trial-by-fire in order to prove the

truth of the Gospel. According to some sources, the Sultan gave Francis permission to visit the

sacred places in the Holy Land and to preach there. Francis and a companion left the Crusader

camp for Acre, from where they embarked for Italy in the latter half of 1220. The Franciscan

Order has been present in the Holy Land almost uninterruptedly since 1217 when Brother Elias

arrived at Acre. It received concessions from the Mameluke Sultan in 1333 with regard to Holy

Places in Jerusalem and Bethlehem, and (so far as concerns the Catholic Church) jurisdictional

privileges from Pope Clement VI in 1342.

Francis preaches to the Sultan in Egypt

The growing Order of friars was divided into provinces and groups were sent to France, Germany,

Hungary, Spain and the East. When receiving a report of the martyrdom of five brothers in

Morocco, Francis returned to Italy via Venice. Cardinal Ugolino di Conti was nominated by the

Pope as the protector of the Order. The friars in Italy at this time were causing problems, and

Francis had to return in order to bring correction to his own followers.

The Franciscan Order had grown at an unprecedented rate, when compared to other religious

orders, but its organizational sophistication had not kept up with this growth and had little more

to govern it than Francis' example and simple rule. To address this shortfall, Francis prepared a

new and more detailed Rule, the "First Rule" or "Rule Without a Papal Bull" (Regula prima Regula

non bullata) which asserted devotion to poverty and the apostolic life. It introduced greater

institutional structure, although this was never officially endorsed by the pope.

On 29 September 1220, Francis handed over the governance of the Order to Brother Peter Catani

at the Porziuncola. However, Peter died five months later, on 10 March 1221, and was buried in

the Porziuncola. When miracles were attributed to the deceased Brother, people started to flock

to the Porziuncola, disturbing the daily life of the Franciscans. Francis then prayed, supposedly

asking the Apostle Peter to stop the miracles. Brother Peter was succeeded by Brother Elias as

Vicar of Francis. Two years later, Francis modified the "First Rule" (creating the "Second Rule" or

"Rule with a Bull"; a "Bull" is a Papal edict), and Pope Honorius III approved it on 29 November

1223. As the official Rule of the order, necessary for what was now a large organisation, it called

on the friars "to observe the Holy Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ, living in obedience without

anything of our own and in chastity." In addition, it set regulations for discipline, preaching, and

entry into the order. Once the Rule was endorsed by the Pope, Francis withdrew increasingly from

external affairs. During 1221 and 1222, Francis crossed Italy, first as far south as Catania in Sicily

and afterwards as far north as Bologna. He retired to a hermitage on Monte Alvernia.

While he was praying on Monte Alvernia, during a forty-day fast in preparation for Michaelmas

(September 29), Francis is said to have had a vision on or about 14 September 1224, the Feast of

the Exaltation of the Cross, as a result of which he received the stigmata, physical marks like

those of the crucified Jesus. Brother Leo, who had been with Francis at the time, left a clear and

simple account of the event, the first definite account of the phenomenon of stigmata. "Suddenly

he saw a vision of a seraph, a six-winged angel on a cross. This angel gave him the gift of the five

wounds of Christ."

Supposedly suffering from these stigmata and from trachoma, Francis received care in several

cities (Siena, Cortona, Nocera) to no avail. In the end, he was brought back to a hut next to the

Porziuncola. Here, in the place where it all began, feeling the end approaching, he spent the last

days of his life dictating his spiritual testament. He died on the evening of 3 October 1226,

singing Psalm 142(141) - "Voce mea ad Dominum".

On 16 July 1228, Francis was proclaimed a "saint" by Pope Gregory IX (the former cardinal Ugolino

di Conti, friend of St Francis and originally Cardinal Protector of the Order). The next day, the

Pope laid the foundation stone for the Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi. He was buried on 25 May

1230, under the Lower Basilica, but his tomb was soon hidden on orders of Brother Elias to protect

it from potential Saracen invaders. His burial place remained unknown until 1818. Pasquale Belli

then constructed a crypt in neo-classical style in the Lower Basilica for his remains. In 1978, the

remains of St. Francis were examined and confirmed by a commission of scholars appointed by

Pope Paul VI, and put in a glass urn in the ancient stone tomb.

Francis believed commoners should be able to pray to God in their own language, and he wrote

often in the dialect of Umbria instead of Latin. His writings are considered to have great literary

and religious value. He is also known as the patron saint of animals, the environment, and is one

of the two patron saints of Italy (along with Catherine of Siena). He is remembered for his love of

the Eucharist and for his sorrow during the Stations of the Cross.

Evaluating the Work of Francis

It has been argued by some that no one was ever as dedicated as Francis to imitating the life and

work of Christ. He and his followers celebrated (and even venerated) poverty. Poverty was so

central to his character that in his last written work, "The Testament", Francis said that absolute

personal and corporate poverty was the essential lifestyle for the members of his order. He

believed that nature itself was the mirror of God. He called all creatures his "brothers" and

"sisters," and even preached to the birds and supposedly persuaded a wolf to stop attacking some

locals if they agreed to feed the wolf. In his "Canticle of the Creatures" ("Praises of Creatures"

or "Canticle of the Sun"), he mentioned the "Brother Sun" and "Sister Moon," the wind and

water, and "Sister Death." He referred to his chronic illnesses as his "sisters." His deep sense of

brotherhood under God embraced others, and he declared that "he considered himself no friend

of Christ if he did not cherish those for whom Christ died." Francis's visit to Egypt and attempted

rapprochement with the Muslim world had far-reaching consequences, long past his own death,

since after the fall of the Crusader Kingdom only Franciscans, of all Catholics, would be allowed

to stay on in the Holy Land and be recognized as "Custodians of the Holy Land" on behalf of the

Catholic Church.

Francis held to the teaching of the Catholic Church, that the world was created good and

beautiful by God but suffers a need for redemption because of the sin of man. He did not

withdraw from the world and focus on nature as an end in itself, but because he believed that the

natural world pointed to the wonder of the Creator. Francis preached to man and beast the

universal ability and duty of all creatures to praise God (a common theme in the Psalms) and the

duty of men to protect and enjoy nature as both the stewards of God's creation and as creatures

ourselves. Many of the stories that surround the life of Francis say that he had a great love for

animals and the environment. His main concern, however, remained the welfare of ordinary

people in the cities; he urged his followers to live in poverty among them.

Perhaps the most famous incident that illustrates Francis' humility towards nature is recounted in

the "Fioretti" ("Little Flowers"), a collection of legends and folklore that sprang up after his death.

It is said that, one day, while Francis was travelling with some companions, they reached a place

in the road where birds filled the trees on either side. Francis told his companions to "wait for me

while I go to preach to my sisters the birds." Legend recounts that he birds surrounded him,

intrigued by the power of his voice, and not one of them flew away.

Another legend from the Fioretti tells that in the city of Gubbio, where Francis lived for some

time, was a wolf "terrifying and ferocious, who devoured men as well as animals". Francis had

compassion upon the townsfolk, and so he went up into the hills to find the wolf. Soon, fear of

the animal had caused all his companions to flee. When he found the wolf, he made the sign of

the cross and commanded the wolf to come to him and hurt no one. Miraculously the wolf closed

his jaws and lay down at the feet of Francis. "Brother Wolf, you do much harm in these parts and

you have done great evil," said Francis. "All these people accuse you and curse you...But brother

wolf, I would like to make peace between you and the people."

Then Francis led the wolf into the town, and surrounded by startled citizens made a pact between

them and the wolf. Because the wolf had "done evil out of hunger, the townsfolk were to feed it

regularly. In return, the wolf no longer preyed upon them or their flocks. In this manner Gubbio

was freed from the menace of the predator. Francis even made a pact on behalf of the town

dogs, that they would not bother the wolf again. Finally, to show the townspeople that they would

not be harmed, Francis blessed the wolf. Hagiographers make much of such legends.

Francis is honored in the Church of England, the Anglican Church of Canada, the Episcopal Church

USA, the Old Catholic Churches, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, and other churches

and religious communities, on 4 October. The Evangelical Church in Germany commemorates St.

Francis' feast day on 3 October, the anniversary of his death.

Some regarded Francis as a madman; others viewed him as one of the greatest examples of how

to live the Christian ideal since Jesus Christ himself. Whether he was really touched by God, or

simply a man misinterpreting hallucinations brought on by mental illness and/or poor health, he

was incredibly sleep-deprived and malnourished - one thing is for certain: Francis of Assisi quickly

became well-known throughout the Christian world. Francis' Christ-like poverty was a radical

notion at the time. The Church was rich, much like the people heading it, which concerned him

(and many others, who felt that the Church's long-held apostolic ideals had eroded).

Francis had set out on a mission to restore Jesus Christ's original values to a decadent Church.

Thousands of followers were soon drawn to him, listening to his sermons and joining in his way of

life; many of his followers became Franciscan friars. Continuously pushing himself in the quest

for spiritual perfection, Francis was soon preaching in up to five villages per day, teaching a new

kind of emotional and personal Christian faith that everyday people could understand. Given his

preaching to animals, he attracted criticism and the nickname "God's fool." But Francis's message

was spread far and wide, and thousands were captivated by what they heard.

Today, Francis has millions of followers across the globe. His following prayer is well known:

Lord, make me an instrument of thy peace. Where there is hatred, let me sow love; where there is injury,

pardon; where there is doubt, faith; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light; where

there is sadness, joy. O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek to be consoled as to console; not

so much to be understood as to understand; not so much to be loved as to love. For it is in giving that we

receive; it is in pardoning that we are pardoned; it is in dying that we awaken to eternal life.

Lord, make me an instrument of thy peace. Where there is hatred, let me sow love; where there is injury,

pardon; where there is doubt, faith; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light; where

there is sadness, joy. O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek to be consoled as to console; not

so much to be understood as to understand; not so much to be loved as to love. For it is in giving that we

receive; it is in pardoning that we are pardoned; it is in dying that we awaken to eternal life.

After the death of Francis his movement began to lose its appeal of simplicity and obedient

imitation of Christ, and to be more closely aligned with the overarching structure of the organized

church. However, the simplicity of his example continues to impact today.

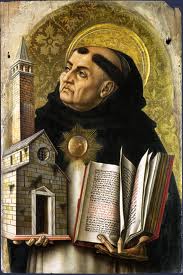

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)

Background

Dominican friar and priest and an influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of

"scholasticism". Aquinas forged a unique synthesis of faith and reason, of ancient philosophy and

sacred Scripture, which decisively influenced Dante and subsequent Catholic tradition.

Aquinas was born in southern Italy, at his father's castle, in 1225, around the time of the death of

Francis of Assisi. He was from a wealthy family. His mother was related to the Holy Roman

Emperors, who ruled southern Italy at this time, and his uncle was the abbot of the monastery at

Monte Cassino, founded by Benedict. Thomas had an older brother who would inherit his father's

castle and farmland, so it was decided that, when he grew up Thomas should become the leader

of the Monte Cassino monastery. This would have been a normal career path for a younger son of

southern Italian nobility.

Thomas started school at the monastery when he was five. He studied there until he was ten, and

then he went to study at the newly founded University of Naples, near his home. While there, he

met some Dominican students and professors who convinced him to change his plans.

The Dominicans wanted to build a form of Christianity that would be more pure and good than

institutionalised Christianity that now was now prevalent - not concerned with money or power,

but where the monks would be poor and devote their lives to study and to helping the poor.

Aquinas left Naples and started traveling to Rome, to become a Dominican monk. His change of

heart did not please his family. His brothers kidnapped him on the way to Rome and dragged him

back to his father's castle, where he was kept locked up for more than a year, in an effort to

convince him to change his mind. They even attempt to compromise him with a prostitute.

Finally the Pope ordered his release and he travelled to Rome and became a Dominican. He was

just seventeen.

In 1244, Thomas was sent to study at a Dominican school in Cologne, Germany, with a famous

teacher, Albertus Magnus (or Albert the Great). In Cologne, fellow-students made fun of him for

being physically big, serious, slow and quiet. They called him the "Dumb Ox". But Albertus saw

that Thomas was smart. When Albertus decided to work at the University of Paris (as Chair of

Theology at the College of Saint James), Aquinas accompanied him. He ended up getting his

doctorate from the University of Paris and teaching theology in various centres of learning. In

February 1265 the newly elected Pope Clement IV summoned Aquinas to Rome to serve as papal

theologian. This same year he was ordered by the Dominican Chapter of Agnani to teach at the

studium conventuale at the Roman convent of Santa Sabina which had been founded in 1222.

Harmonising Ancient and Christian Thinking

For many years before Thomas Aquinas was born, men like Ibn Sina (the most famous of the

philosopher-scientists of Islam, 980-1037). and Ibn Rushd (the most famous Spanish Muslim

philosopher; known in the Latin West as Averroes, 1126-1198) in the Abbasid Empire had been

reading the Koran, and reading the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BC; student of Plato and

teacher of Alexander the Great), and trying to find ways to get these two important figures to

agree with each other. Both were seeking to explain how the universe worked, in a way that

honoured both God and science, without leaving contradictions.

For many in the church (including the mystics), who did not understand the Biblical principle of

general revelation, and the fact that God can speak through the faculty of reason reference to

Aristotle was a challenge, that went something like this:

Knowledge is a good thing

Good things come from God

Aristotle knew a great deal

But Aristotle was a pagan.

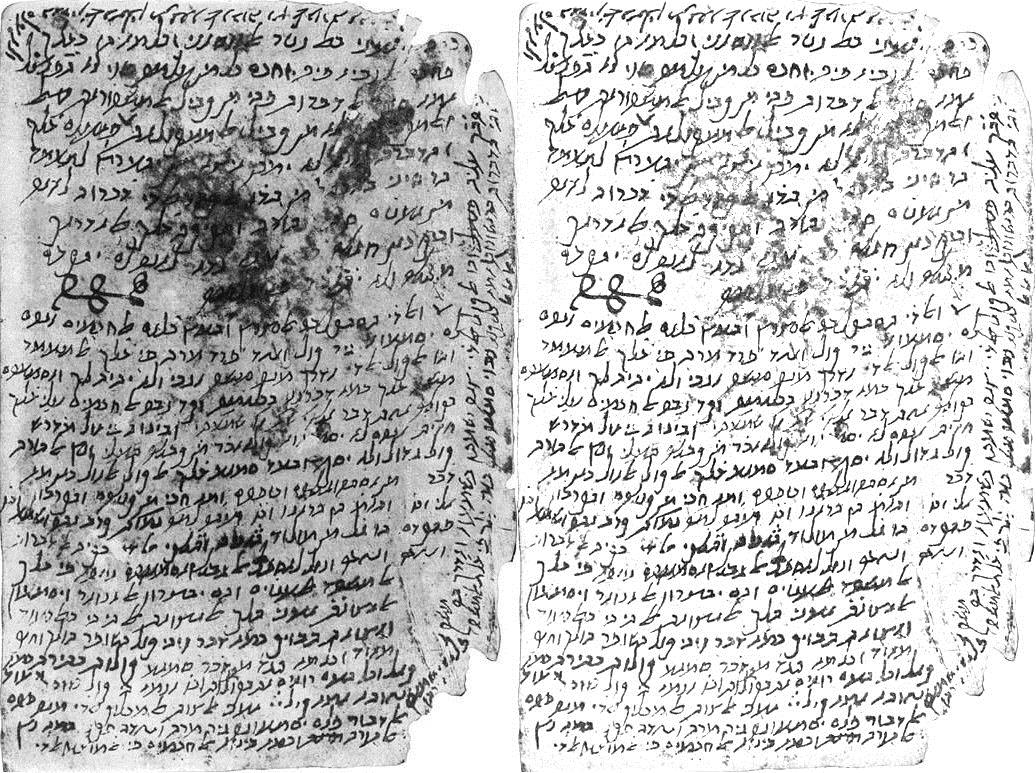

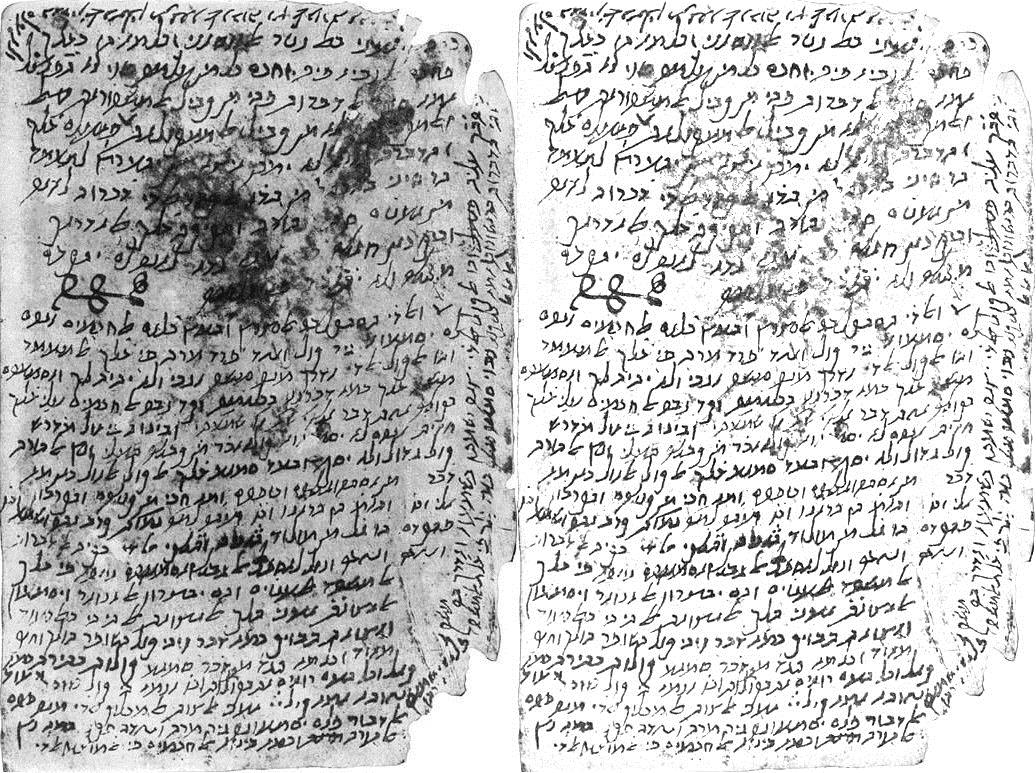

In the 1100s, the Jewish philosopher Maimonides (1135-1204; preeminent medieval Spanish,

Sephardic Jewish philosopher, astronomer and one of the most prolific and influential Torah

scholars and physicians of the Middle Ages; lived much of his life in Cordoba, Spain) tried to do

the same thing for Judaism, finding how Aristotle could work with the Torah (the Jewish Bible).

Maimonides & his works

When Thomas Aquinas was a young man, studying in Cologne and Paris in the 1200s, he read Latin

translations of Maimonides, Ibn Rushd, and Ibn Sina, who had sought to harmonise Aristotle (and

ideas around faith and reason) with Judaism/the Talmud and Islam and decided to do the same

thing - he would figure out how Aristotle worked with Christian beliefs.

Since the end of the Roman Empire, hardly anyone in Europe had read Aristotle. At the same

time, Aquinas wanted to show that Christianity was the true religion, not Islam or Judaism.

Aquinas agreed with Ibn Rushd or Maimonides about some things. He agreed with Maimonides that

God didn't really look like a man, but was more like a spirit or idea. Ibn Rushd thought that when

you died, your soul mixed back into one big soul, and some Christian scholars in Paris agreed with

him, but Aquinas insisted that each soul lived on after death. His belief in the immortality of the

soul was in line with Biblical teaching (eg Ecclesiastes 12:7, 1 Corinthians 15).

Aquinas disagreed with both Ibn Rushd and Maimonides about why people should be good.

Maimonides said that God had given people practical laws to show them the way to happiness on

earth - even if God had not been involved, these rules would show the way to happiness. Ibn

Rushd said (thinking that individual souls did not survive after death) that if you lived by God's

rules (or Shari'a) you would be happy on earth, although intelligent people who also studied

philosophy might find a truer happiness. But Aquinas thought that people should mainly be trying

to achieve happiness after death, by being with God in Heaven, ie follow God's laws because that

is the way to Heaven. He taught that, to get to Heaven, one had to truly love God, and if a

person loved God, he or she would naturally also love goodness, because God is good.

Aquinas Refines His Thinking

Intensely interested in Aristotle (4th century BC), as well as Plato, Paul, and Augustine, Thomas

believed that human thought can take us a long way towards wisdom and truth, although it must

always be supplemented by the central mystery of "revelation". His writings contain classic

statements of doctrine about angels, the Incarnation, the Trinity, sacraments and the soul and

also discussions on choice, creation and conscience, law, logic and the purpose of life.

Thomas' approach was as follows:

- identify an issue

- develop a response based on Biblical teaching

- draw on the philosophers, especially Aristotle (or Averroes, or Maimonides) - some

Christian scholars thought that Aristotle should be banned

- harmonise them and develop a response, on the premise that faith & revelation (Scripture

and God's revelation to men) and reason (the philosophers) are logically compatible

- this (dialectic) approach always carried a risk that the understood Biblical view would be

at the expense of others, for faith and reason are not always compatible; it also ran the

risk the basic Biblical teaching would be over-allegorised; some argued that God cannot be

understood by reason.

Aquinas was a prolific writer (his works filled eighteen volumes) and the chief teacher of the

Catholic Church; he was arguably the greatest Christian philosopher. His chief works were

commentaries on most of the books of the Bible, Summa Contra Gentiles, an apologetic for

Dominican missionaries to Jews, Muslims, and heretics in Spain and Summa Theologica, the

theology that supplanted Lombard's Sentences as the chief theological work of the Middle Ages.

Thomas Aquinas also did not always manage to make Aristotle agree with Christian ideas. Aristotle

had seen the universe as eternal, with no beginning or end. He believed that the universe had

always been there and would continue forever. Christianity told Aquinas that God had created the

universe, and that it would end with the Last Judgment of Christ. Like Maimonides, Aquinas took

the Judeo-Christian view that there had to be something that started off the universe (creation),

and that this was one of the proofs that there really was a God.

Thomas Aquinas also did not always manage to make Aristotle agree with Christian ideas. Aristotle

had seen the universe as eternal, with no beginning or end. He believed that the universe had

always been there and would continue forever. Christianity told Aquinas that God had created the

universe, and that it would end with the Last Judgment of Christ. Like Maimonides, Aquinas took

the Judeo-Christian view that there had to be something that started off the universe (creation),

and that this was one of the proofs that there really was a God.

Aquinas spent the rest of his life traveling between Naples, Paris and Rome, preaching, writing,

and helping to solve political and religious arguments. Dante heard him preach in Florence, and

was influenced. In 1054, the Great Schism had taken place between the Latin Church following

the Pope in the West, and the four patriarchates in the East (Orthodox Church). Looking to find a

way to reunite the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church, Pope Gregory X

convened the Second Council of Lyon to be held on 1 May 1274 and summoned Thomas to attend.

At the meeting, Thomas's work for Pope Urban IV concerning the Greeks, Contra errores

graecorum, was to be presented. On his way to the Council, riding on a donkey along the Appian

Way, Thomas struck his head on the branch of a fallen tree and became seriously ill. He was then

quickly escorted to Monte Cassino to convalesce. After resting for a while, he set out again, but

stopped at the Cistercian Fossanova Abbey after again falling ill. The monks nursed him for

several days, and as he received his last rites he prayed: "I receive Thee, ransom of my soul. For

love of Thee have I studied and kept vigil, toiled, preached and taught...." He died on 7 March

1274 while giving commentary on the Song of Songs. He was fifty years old.

Thomas' writings were subsequently drawn on heavily by the Catholic Church in understanding

apologetics, and formulating decrees during the Council of Trent (1534-63). In 1567, Pope Pius V

proclaimed Thomas Aquinas a Doctor of the Church and ranked him with Ambrose, Augustine of

Hippo, Jerome and Gregory. In an encyclical on 4 August 1879, Pope Leo XIII stated that Thomas'

theology was a definitive exposition of Catholic doctrine. He directed the clergy to take these

teachings as the basis of their theological positions. Leo XIII also decreed that Catholic seminaries

and universities teach Thomas' doctrines, and where Thomas did not speak on a topic, they were

"to teach conclusions that were reconcilable with his thinking." In 1880, Aquinas was declared

patron of all Catholic educational establishments.

In modern times, his works are included in study programs for those seeking ordination as priests

or deacons, as well as those in religious formation and for other students of sacred disciplines.

Summary of Thomism

Thomas never considered himself a philosopher; he criticized philosophers, whom he saw as

pagans, for "falling short of the true and proper wisdom to be found in Christian revelation." He

respected Aristotle, so much so that in the Summa, he often cites Aristotle, as "the Philosopher."

Much of his work deals with philosophical topics. Thomas' philosophical thought has exerted

enormous influence on subsequent Christian theology, especially that of the Catholic Church (eg

teaching base for the growth of the Jesuits), extending to Western philosophy in general. Thomas

stands as a vehicle and modifier of Aristotelianism and Neo-Platonism. Thomas wrote several

important commentaries on Aristotle's works.

Thomas believed "that for the knowledge of any truth whatsoever man needs divine help, that the

intellect may be moved by God to its act." However, he believed that human beings have the

natural capacity to know many things without special divine revelation, even though such

revelation occurs from time to time, "especially in regard to such (truths) as pertain to faith." But

this is the light that is given to man by God according to man's nature: "Now every form bestowed

on created things by God has power for a determined actuality, which it can bring about in

proportion to its own proper endowment; and beyond which it is powerless, except by a

superadded form, as water can only heat when heated by the fire. And thus the human

understanding has a form, viz. intelligible light, which of itself is sufficient for knowing certain

intelligible things, viz. those we can come to know through the senses."

Thomas' ethics are based on the concept of "first principles of action." In his Summa theologiae,

he wrote: "Virtue denotes a certain perfection of a power. Now a thing's perfection is considered

chiefly in regard to its end. But the end of power is act. Wherefore power is said to be perfect,

according as it is determinate to its act." Thomas also greatly influenced Catholic

understandings/teaching on mortal and venial sins.

Thomas viewed theology as a science, consisting of Scripture and Catholic tradition. These

sources were produced by the revelation of God to individuals and groups through history. Faith

and reason, while distinct but related, are the primary tools for processing theology. He blended

Greek philosophy and Christian doctrine by suggesting that rational thinking and the study of

nature, like revelation, were valid ways to understand truth about God. According to Thomas,

God reveals himself through nature; to study nature is to study God. The goals of theology, in his

mind, are to use reason to grasp truth about God and experience salvation through that truth.

Thomas believed that truth is known through reason (natural revelation) and faith (supernatural

revelation). Supernatural revelation has its origin in the inspiration of the Holy Spirit and is made

available through the teaching of the prophets, summed up in Scripture, and transmitted by the

Magisterium, the sum of which is called "Tradition". Natural revelation is the truth available to all

people through their human nature and powers of reason. For example, he felt this applied to

rational ways to know the existence of God.

Thomas taught that, though one may deduce the existence of God and his attributes (Unity, Truth,

Goodness, Power, Knowledge) through reason, certain specifics may be known only through the

special revelation of God in Jesus Christ. The major theological components of Christianity, such

as the Trinity and the Incarnation, are revealed in the teachings of the Church and the Scriptures

and may not otherwise be deduced.

Thomas believed that faith and reason complement rather than contradict each other, each giving

different views of the same Truth.

1. Creation

As a Catholic, Thomas believed that God is the "maker of heaven and earth, of all that is visible

and invisible." Like Aristotle, he believed that life could form from non-living material or plant

life, a process known as spontaneous generation.

2. Just War

Augustine of Hippo agreed strongly with the conventional wisdom of his time, that Christians

should be pacifists philosophically, but that they should use defence as a means of preserving

peace in the long run. He argued that pacifism did not prevent the defence of innocents. The

pursuit of peace might require fighting to preserve it in the long-term. Such a war must not be

pre-emptive, but defensive, to restore peace.

Thomas Aquinas, centuries later, used the authority of Augustine's arguments in an attempt to

define the conditions under which a war could be just. He laid these out in Summa Theologica:

- First, war must be for a good and just purpose rather than the pursuit of wealth or power.

- Second, just war must be waged by a properly instituted authority such as the state.

- Third, peace must be a central motive even in the midst of violence.

Thomas believed that expansionist wars, wars of pillage, wars to convert infidels or pagans, and

wars for glory are all inherently unjust.

3. Nature of God

Thomas believed that the existence of God can be proven. His approaches followed Maimonides.

His proofs for the existence of God take some of Aristotle's assertions concerning principles of

being. For Thomas, God as first cause comes from Aristotle's concept of the unmoved mover and

asserts that God is the ultimate cause of all things.

Nature of the Trinity

Thomas argued that God, while perfectly united, also is perfectly described by Three Interrelated

Persons. These three persons (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) are constituted by their relations

within the essence of God. Thomas wrote that the term "Trinity" "does not mean the relations

themselves of the Persons, but rather the number of persons related to each other; and hence it

is that the word in itself does not express regard to another. The Father generates the Son (or the

Word) by the relation of self-awareness. This eternal generation then produces an eternal Spirit

"who enjoys the divine nature as the Love of God, the Love of the Father for the Word."

This Trinity exists independently from the world. It transcends the created world, but the Trinity

also decided to give grace to human beings. This takes place through the Incarnation of the Word

in the person of Jesus Christ and through the indwelling of the Holy Spirit within those who have

experienced salvation.

4. Nature of Jesus Christ

In the Summa Theologica, Thomas begins his discussion of Jesus Christ by recounting the biblical

story of Adam and Eve and describing the negative effects of original sin. The purpose of Christ's

Incarnation was to restore human nature by removing "the contamination of sin", which humans

cannot do by themselves. "Divine Wisdom judged it fitting that God should become man, so that

thus one and the same person would be able both to restore man and to offer satisfaction."

Thomas argued in favour of the satisfaction view of atonement; that is, that Jesus Christ died "to

satisfy for the whole human race, which was sentenced to die on account of sin."

Thomas stated that Jesus was truly divine and not simply a human being, that the fullness of God

was an integral part of Christ's existence; that Christ had a truly human (rational) soul as well. He

argued that these two natures existed simultaneously yet distinguishably in one real human body,

that "Christ had a real body of the same nature of ours, a true rational soul, and, together with

these, perfect Deity." This is consistent with Colossians.

Ironically, he also (erroneously, echoing Athanasius of Alexandria) said that "The only begotten Son

of God...assumed our nature, so that he, made man, might make men gods."

5. The Goal of Human Life

Thomas identified the goal of human existence as union and eternal fellowship with God. This

goal is achieved through the beatific vision, in which a person experiences perfect, unending

happiness by seeing the essence of God. The vision occurs after death as a gift from God to those

who in life experienced salvation and redemption through Christ. This approach is confusing.

Thomas stated that an individual's will must be ordered toward right things, such as love, peace,

and holiness. He saw this orientation as also the way to happiness. "Those who truly seek to

understand and see God will necessarily love what God loves. Such love requires morality and

bears fruit in everyday human choices".

6. Treatment of Heretics

Thomas Aquinas belonged to the Dominicans, who began as an order dedicated to the conversion

of the Albigensians and other factions, at first by peaceful means; later the Albigensians were

dealt with effectively but violently during the Albigensian Crusade.

Heresy was a capital offense against the secular law of most European countries of the 13th

century, which had a limited prison capacity. Theft, forgery, fraud, and other such crimes were

also capital offenses; Thomas supported excommunication and capital punishment for heretics.

7. The Afterlife and Resurrection

Thomas taught that the soul continues to exist after the death of the body. He also believed in

heaven and hell described in scripture and church dogma.

Observations

- reciting creeds without thinking about their content ends up being merely formulaic;

during the Middle Ages such approaches often led to genuine Christian thinkers being

interdicted and labelled "heretics", excommunicated, victims of inquisitions

- it is good to explore faith and explain what we believe - it is possible to explain Christian

belief without explaining it away; practical Christianity involves faith seeking

understanding (rather than the other way around, given the need for revelation, cf Acts

8:30-34)

- the ability to reason is God-given - whether the conclusions are correct depends on the

state of the individual (faith versus unbelief); it does not imply questioning or doubting

God

- reason that links with revelation can be instrumental in effective apologetics and dealing

with controversy

- Bible-based dialectic can be an effective tool to rebut false teaching

- the church's witness needs Francis types (servants) and Thomas types (theologians)

Lord, make me an instrument of thy peace. Where there is hatred, let me sow love; where there is injury,

pardon; where there is doubt, faith; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light; where

there is sadness, joy. O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek to be consoled as to console; not

so much to be understood as to understand; not so much to be loved as to love. For it is in giving that we

receive; it is in pardoning that we are pardoned; it is in dying that we awaken to eternal life.

Lord, make me an instrument of thy peace. Where there is hatred, let me sow love; where there is injury,

pardon; where there is doubt, faith; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light; where

there is sadness, joy. O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek to be consoled as to console; not

so much to be understood as to understand; not so much to be loved as to love. For it is in giving that we

receive; it is in pardoning that we are pardoned; it is in dying that we awaken to eternal life.

Thomas Aquinas also did not always manage to make Aristotle agree with Christian ideas. Aristotle

had seen the universe as eternal, with no beginning or end. He believed that the universe had

always been there and would continue forever. Christianity told Aquinas that God had created the

universe, and that it would end with the Last Judgment of Christ. Like Maimonides, Aquinas took

the Judeo-Christian view that there had to be something that started off the universe (creation),

and that this was one of the proofs that there really was a God.

Thomas Aquinas also did not always manage to make Aristotle agree with Christian ideas. Aristotle

had seen the universe as eternal, with no beginning or end. He believed that the universe had

always been there and would continue forever. Christianity told Aquinas that God had created the

universe, and that it would end with the Last Judgment of Christ. Like Maimonides, Aquinas took

the Judeo-Christian view that there had to be something that started off the universe (creation),

and that this was one of the proofs that there really was a God.